New Ways of "Recognizing" Biological Molecules

Suwannar Kawila/Canva

Date of publication:

For the normal course of all life processes, the cooperation of multiple biomolecules is required, such as various proteins, DNA molecules, etc. It is crucial that specific molecules form mutual 'contacts' to execute a particular biological process. But how do different molecules "know" which ones should meet?

This is the so-called problem of molecular recognition, which has a long history. In the early 20th century, German chemist and Nobel laureate Emil Fischer defined it. He hypothesized that molecules have specific shapes, allowing only those with complementary shapes to recognize each other, much like a key and a lock. Although Fischer did not know exactly what molecules looked like or their shapes at that time, his hypothesis was correct, and in many cases, molecular recognition operates on the key-lock analogy.

Recently, it has been shown that a significant portion of proteins do not have defined shapes or have fluid, changing forms (so-called intrinsically disordered proteins). How does molecular recognition occur in such cases, given that the key-lock analogy is based on clear, fixed shapes of molecules?

Researchers Asst. Prof. Dr. San Hadži, Zala Živič, Uroš Zavrtanik, and Prof. Dr. Jurij Lah from the Department of Physical Chemistry at the Faculty of Chemistry and Chemical Technology, University of Ljubljana, together with colleagues from the National Institute of Chemistry and the University of Brussels (VUB), published an article in the journal Nature Communications titled "Fuzzy recognition by the prokaryotic transcription factor HigA2 from Vibrio cholerae". In this study, the authors explained how recognition occurs between a protein with a fluid, changing structure and a DNA molecule. The editors of Nature Communications highlighted the study in the Editors’ Highlights section.

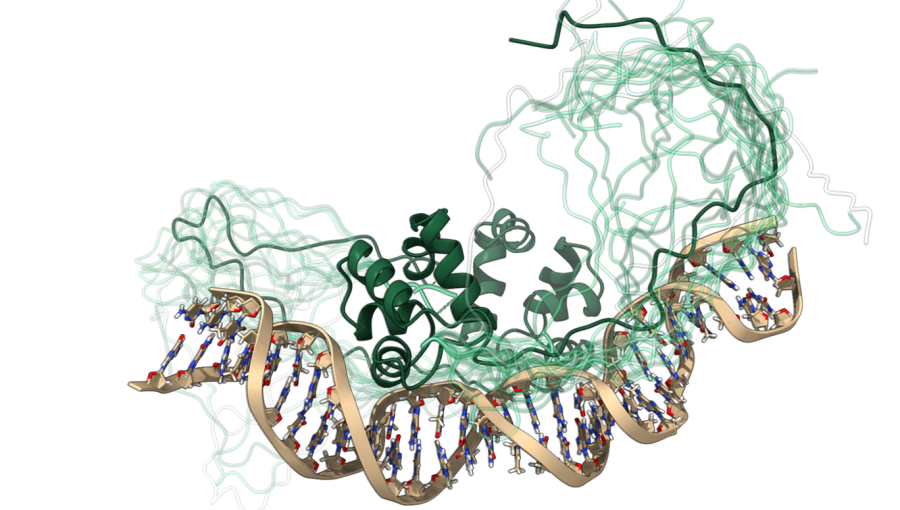

In their research, the authors examined the binding of the bacterial protein HigA2 to DNA. They found that the key is the cooperation between the globular DNA-binding domain of the protein and its intrinsically disordered region, which interacts with DNA in a "fuzzy" manner. Using methods such as nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS), isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC), and mutagenesis, they precisely defined the biophysical and structural characteristics of this type of soft interaction, discovering that the disordered region hovers over the DNA, forming transient contacts through specific amino acid "islands." Unlike previously described fuzzy interactions in the literature, a higher degree of sequence specificity is observed in this case.

Interestingly, the same sequence of amino acids on the HigA2 protein can establish a completely different mode of interaction when it binds to a protein target. In this case, binding occurs through strong, specific interactions and is coupled with the sequence folding into a helix (induced fit binding). This example shows how an unstructured amino acid sequence can enable different modes of molecular recognition and thus perform multiple biological functions.

The research was co-financed by the Slovenian Research Agency through the program group Physical Chemistry P1-0201 (M. Lukšič) and project J1-50026 (S. Hadži). The article is available in open access: Nature Communications.